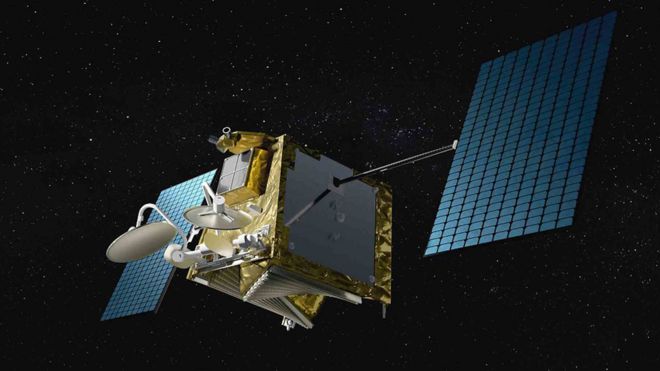

Broadband is to be beamed to every corner of the earth from space following the biggest rocket campaign in the history of spaceflight. The network will comprise at least 600 spacecraft in the first instance, but could eventually encompass more than 2,000. The aim is to deliver broadband links from orbit to every corner of the globe.

In particular, the project wants every school to have a connection. Building so large a constellation requires a step-change in the manufacture of satellites - especially for Airbus. It can take Europe’s biggest space company many months and hundreds of millions of dollars to build some of today’s specialist platforms. But for the OneWeb venture, it is all about high volume and low cost.

That means new assembly line methods akin to those in factories producing cars and planes. The idea is to turn out three units per shift at well less than a million dollars apiece. The boss of Airbus, Tom Enders, concedes he initially thought the OneWeb concept to be fantasy.

"Everything in space as you know traditionally has been 'gold-plated'; it had to work perfectly, [and have] the most expensive materials, etc.

"Here, we’ve had to go other ways, to be really commercial and calculating according to the target cost because that is very decisive in the whole business case for OneWeb," he told BBC News.

Airbus and OneWeb have inaugurated the first assembly line in Toulouse, France. Two further lines will be set up in a soon-to-open factory complex in Florida. The most obvious difference you notice between these new lines and the conventional satellite cleanroom is the trolley robot, which moves the developing satellites between the various work stations. But the "revolution" here goes far beyond automation; it requires a whole chain of suppliers and their components to scale their work to a different game plan.

The first 10 satellites to come off the Toulouse assembly line have a deadline to launch in April next year.

Another batch will follow into orbit around November. And then the launch cadence will kick on apace. The establishment of the OneWeb constellation requires the greatest rocket campaign in the history of spaceflight. More than 20 Soyuz vehicles have been booked to throw clusters of 32-36 satellites into a web some 1,200km above the Earth.

There should be just under 300 on station by the end of 2020, the start of 2021; more than 600 about a year or so later; and then over 800 by the middle of the decade.

OneWeb and Airbus are not the only companies planning a mega-constellation in the sky. SpaceX, Boeing, ViaSat and others have all sought regulatory approval. But not everyone will succeed in getting the necessary multi-billion-dollar financing, and Airbus believes the OneWeb concept has first-mover advantage.

Equity of $1.7bn has already been raised, and talks are ongoing to secure the loans needed to complete the roll-out. OneWeb describes itself as a "truly global company" but it has company registration in the UK's Channel Islands. And, as such, it must deal with the UK Space Agency as the licensing authority.

"A lot of our revenues are going to flow through the UK. So, from an economic perspective, it is going to be very important for the UK," said OneWeb CEO Eric Béranger. "And when you have people locally, you are also fostering an ecosystem. And I think the UK being at the forefront of regulatory thinking on constellations will foster an environment that puts the UK ahead of many countries."

One aspect that the UKSA is sure to take a keen interest in is debris mitigation.

There is considerable concern that a proliferation of multi-satellite networks could lead to large volumes of junk and a cascade of collisions. The fear is that space could eventually become unusable.

A recent study - sponsored by the European Space Agency and supported by Airbus itself - found that the new constellations would need to de-orbit their old, redundant spacecraft within five years or run the risk of seriously escalating the probability of objects hitting each other. Brian Holz, who is CEO of the OneWeb/Airbus manufacturing joint venture, said the ambition of his constellation was to set new standards in debris mitigation.

"We can bring down the satellites and re-enter within two years; we've made that commitment," he told BBC News. "We've put extra hardware into the system to improve the reliability of that de-orbit process."

We're also committing to put a small adapter device on to each spacecraft that will allow those spacecraft, in the small probability that one of them dies on the way down, to be grabbed by a small chase vehicle and pulled out of orbit."

Time will tell how disruptive the new manufacturing approaches adopted in Toulouse will be to the satellite industry as a whole. Airbus and OneWeb hope also to be making satellites for other companies on their assembly lines. But not every platform in the sky will require such volumes and a good number of spacecraft will still need the bespoke treatment.

"Not everything here is application to the whole space industry. When we launch to Jupiter, there are things that will remain gold-plated whether we like it or not.”

Unless of course we start to manufacture 900 satellites to go to Jupiter but this is not the case today,” said Nicolas Chamussy, who runs the satellite division of Airbus.

Via BBC

No comments