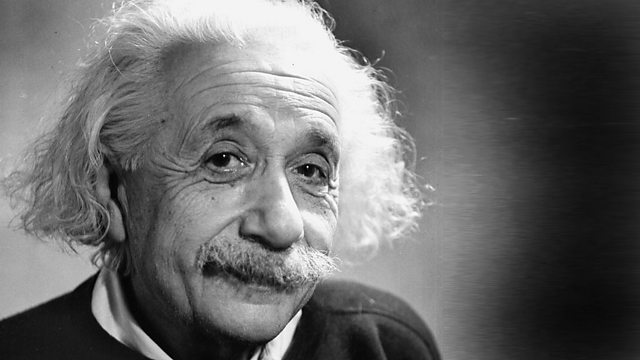

We honour Einstein for developing the special theory of relativity. Time is the fourth dimension and nothing travels faster than the speed of light, although he did not develop the equations. That was the interpretation, the story told by the equations, and this holds true for every other physics theory as well. It's different with quantum mechanics. We are in possession of the quantum mechanical equations, but we cannot agree on their interpretation.

Since Schrodinger's equation is the most well-known, we can

turn the handle and derive numbers from it, but the narrative, the story, and

the explanation are still up for debate. That bothers me, too. When quantum

mechanics emerged, it wasn't because physicists were sitting around scratching

their heads wondering if there must be a deeper understanding of the nature of

reality. By the end of the 19th century, it was already known that we needed

some new physics to explain mysterious phenomena, such as X-ray-like radio

activity, that energy seemed to be coming out of nowhere, to understand the

behaviour or the structure of the atom.

We'll think of quantum mechanics. It was imposed upon

physicists as a result of mysterious experimental results. The world is hazy

and probabilistic. Particles aren't discrete, small lumps, and they

occasionally act like dispersed waves of probability. Atoms can have two

energies at once, electrons may be in two positions at once, and nothing ever

behaves in a single manner for sure. Actually, it's much lower than anything we

can picture or fathom.

When you get down to the scale of individual cells or

bacteria or, for that matter, a billionth of a metre, you start to experience

the fuzziness of the quantum world. As an example, consider a tennis ball that

is subject to Newtonian mechanics. As you get smaller and smaller, you will

eventually encounter this fuzziness.

The pioneers of quantum mechanics, including the Danish

physicist Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Wolfgang Pauli, were active in the

1920s. Eventually they came to the realisation that while they could anticipate

the outcomes of measurements, the link to the outside world could only be made

by looking. So the "shut up and compute interpretation," or more

properly the "Copenhagen narrative," is how they got away with not

needing a story. However, many physicists today, including myself, claim that

this story is simply a denial strategy.

By the way, Einstein was quite upset with this, he remarked,

"No, physics' role is to know and comprehend how the universe works, not

only to anticipate the outcomes of tests and have such an operationalist

perspective. Okay, while it is helpful, it doesn't really help us comprehend

anything." We still require a story for this reason. The current world is

largely due to quantum mechanics understanding and Einstein's ideas of

relativity.

We wouldn't have gained a grasp of materials and how they

conduct electricity, meaning we wouldn't have been able to comprehend

semiconductors or create silicon chips, which would have prevented the

development of computers. Without our grasp of quantum mechanics, I would not

be speaking in this medium right now. The quantum universe has other features,

nevertheless, that are more enigmatic.

For instance, quantum entanglement proposes that, let's say,

two electrons that are separated in space can yet act in unison. There are

conjectural hypotheses on the possibility that quantum entanglement connects

space itself. Even the brightest quantum physicists don't fully understand what

happens inside their smartphones, but since we will be developing concepts like

quantum cryptography, quantum computing, and quantum sensors that will have an

impact on how we live our daily lives, we do need to have a basic understanding

of the science in order to know who and what to believe.

We uncover greater secrets when we remove the layers of the

onion covering reality's essence. But while it's true that we're always

learning, getting wiser, and understanding a lot more about the way the world

works now, it doesn't follow that we've come to the end of the path. No, I

believe there will be more craziness in the future, and that's fantastic. I'm

eager for it.

No comments